https://www.doctorshealthpress.com/food ... nfections/

And most importantly ........."Pee like a race horse"

Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)

Forum rules

Be Polite!!

This forum is for discussions that are NOT related to the US Hawks. This area is provided for the convenience of our members, but the US Hawks specifically does not endorse any comments posted in this forum.

Be Polite!!

This forum is for discussions that are NOT related to the US Hawks. This area is provided for the convenience of our members, but the US Hawks specifically does not endorse any comments posted in this forum.

Re: Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)

Sometimes you gotta' push the stick forward while you're lookn' at the ground

-

Craig Muhonen - Contributor

- Posts: 944

- Joined: Tue Nov 05, 2019 9:58 pm

- Location: The Canyons of the Ancients

Re: Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)

https://www.inputmag.com/tech/kinsa-cor ... -more-data

Kinsa’s smart thermometer is proving social distancing works. Now it needs more data.

-

brianscharp - Contributor

- Posts: 304

- Joined: Tue Nov 11, 2014 12:49 pm

Re: Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)

https://www.inputmag.com/tech/kinsa-cor ... -more-data

Each household , each individual , mapping out a plan of attack to fight this outbreak, is a "core value.

This outbreak will most likely , physically affect the grandparents the most, so , get on the phones and pay attention to them, and tell them (maybe one last time) that you Love them.

More research:

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articl ... 6#benefits

TIP YOUR SERVICE PROVIDERS WELL

Each household , each individual , mapping out a plan of attack to fight this outbreak, is a "core value.

This outbreak will most likely , physically affect the grandparents the most, so , get on the phones and pay attention to them, and tell them (maybe one last time) that you Love them.

More research:

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articl ... 6#benefits

TIP YOUR SERVICE PROVIDERS WELL

Sometimes you gotta' push the stick forward while you're lookn' at the ground

-

Craig Muhonen - Contributor

- Posts: 944

- Joined: Tue Nov 05, 2019 9:58 pm

- Location: The Canyons of the Ancients

Re: Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)

Mark Levin made a good argument tonight regarding the distinction between infections and cases of the virus. The death statistics are typically quoted in terms of known cases. But the number of actual infections is likely many times (maybe tens of times) higher than the number of known cases. So the actual death rate per infection is likely much lower than what is being quoted based on "cases".

The countries that have implemented wide-spread testing will therefore report better death statistics than countries who report deaths based on cases.

Thanks Mark. Your explanation was very clear.

The countries that have implemented wide-spread testing will therefore report better death statistics than countries who report deaths based on cases.

Thanks Mark. Your explanation was very clear.

Join a National Hang Gliding Organization: US Hawks at ushawks.org

View my rating at: US Hang Gliding Rating System

Every human at every point in history has an opportunity to choose courage over cowardice. Look around and you will find that opportunity in your own time.

View my rating at: US Hang Gliding Rating System

Every human at every point in history has an opportunity to choose courage over cowardice. Look around and you will find that opportunity in your own time.

-

Bob Kuczewski - Contributor

- Posts: 8396

- Joined: Fri Aug 13, 2010 2:40 pm

- Location: San Diego, CA

Re: Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)

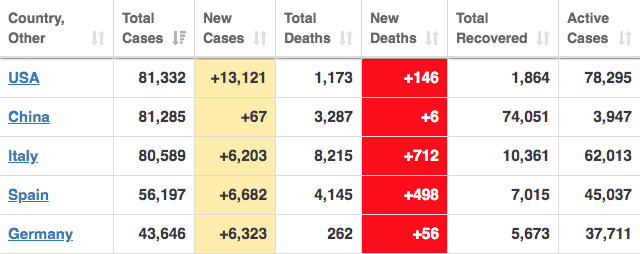

More perspective from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus

| Country | Deaths | Deaths/Million | Deaths/Million |

| San Marino | 21 | 619 | ... |

| Italy | 7,503 | 124 | ... |

| Spain | 3,647 | 78 | ... |

| Iran | 2,077 | 25 | |

| Netherlands | 356 | 21 | |

| France | 1,331 | 20 | |

| Switzerland | 153 | 18 | |

| Belgium | 178 | 15 | |

| Cayman Islands | 1 | 15 | |

| Andorra | 1 | 13 | |

| Luxembourg | 8 | 13 | |

| UK | 465 | 7 | |

| Iceland | 2 | 6 | |

| Denmark | 34 | 6 | |

| Channel Islands | 1 | 6 | |

| Sweden | 62 | 6 | |

| Curaçao | 1 | 6 | |

| Austria | 34 | 4 | |

| Portugal | 43 | 4 | |

| Norway | 14 | 3 | |

| USA | 1,032 | 3 | |

| S. Korea | 131 | 3 | |

| Martinique | 1 | 3 | |

| Germany | 206 | 2 | |

| Ireland | 9 | 2 | |

| Slovenia | 5 | 2 | |

| Bahrain | 4 | 2 | |

| Guadeloupe | 1 | 2 | |

| Panama | 8 | 2 | |

| Cyprus | 3 | 2 | |

| Montenegro | 1 | 2 | |

| Greece | 22 | 2 | |

| Ecuador | 29 | 2 | |

| China | 3,287 | 2 | |

| Albania | 5 | 2 | |

| Mauritius | 2 | 2 | |

| Cabo Verde | 1 | 2 | |

| Lithuania | 4 | 1 | |

| Canada | 36 | 1 | |

| North Macedonia | 3 | 1 | |

| Hungary | 10 | 1 | |

Join a National Hang Gliding Organization: US Hawks at ushawks.org

View my rating at: US Hang Gliding Rating System

Every human at every point in history has an opportunity to choose courage over cowardice. Look around and you will find that opportunity in your own time.

View my rating at: US Hang Gliding Rating System

Every human at every point in history has an opportunity to choose courage over cowardice. Look around and you will find that opportunity in your own time.

-

Bob Kuczewski - Contributor

- Posts: 8396

- Joined: Fri Aug 13, 2010 2:40 pm

- Location: San Diego, CA

Re: Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)

https://www.politico.com/news/2020/03/2 ... cil-149285

Trump team failed to follow NSC’s pandemic playbook

https://politico-dispatch.simplecast.co ... t-in-sight

https://www.theatlantic.com/health/arch ... nd/608719/

How the Pandemic Will End

Trump team failed to follow NSC’s pandemic playbook

https://politico-dispatch.simplecast.co ... t-in-sight

https://www.theatlantic.com/health/arch ... nd/608719/

How the Pandemic Will End

A global pandemic of this scale was inevitable. In recent years, hundreds of health experts have written books, white papers, and op-eds warning of the possibility. Bill Gates has been telling anyone who would listen, including the 18 million viewers of his TED Talk. In 2018, I wrote a story for The Atlantic arguing that America was not ready for the pandemic that would eventually come. In October, the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security war-gamed what might happen if a new coronavirus swept the globe. And then one did. Hypotheticals became reality. “What if?” became “Now what?”

As my colleagues Alexis Madrigal and Robinson Meyer have reported, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention developed and distributed a faulty test in February. Independent labs created alternatives, but were mired in bureaucracy from the FDA. In a crucial month when the American caseload shot into the tens of thousands, only hundreds of people were tested. That a biomedical powerhouse like the U.S. should so thoroughly fail to create a very simple diagnostic test was, quite literally, unimaginable. “I’m not aware of any simulations that I or others have run where we [considered] a failure of testing,” says Alexandra Phelan of Georgetown University, who works on legal and policy issues related to infectious diseases.

RELATED STORIES

A hand holding an empty vial

The 4 Key Reasons the U.S. Is So Behind on Coronavirus Testing

How the Coronavirus Became an American Catastrophe

This Is How We Can Beat the Coronavirus

The testing fiasco was the original sin of America’s pandemic failure, the single flaw that undermined every other countermeasure. If the country could have accurately tracked the spread of the virus, hospitals could have executed their pandemic plans, girding themselves by allocating treatment rooms, ordering extra supplies, tagging in personnel, or assigning specific facilities to deal with COVID-19 cases. None of that happened. Instead, a health-care system that already runs close to full capacity, and that was already challenged by a severe flu season, was suddenly faced with a virus that had been left to spread, untracked, through communities around the country. Overstretched hospitals became overwhelmed. Basic protective equipment, such as masks, gowns, and gloves, began to run out. Beds will soon follow, as will the ventilators that provide oxygen to patients whose lungs are besieged by the virus.

Bob Kuczewski wrote:As for what President Trump "could have" or "should have" done, hindsight will always be 20/20. But even with 20/20 hindsight, I don't see any decisions that would have significantly altered the trajectory of this disease.

-

brianscharp - Contributor

- Posts: 304

- Joined: Tue Nov 11, 2014 12:49 pm

Re: Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)

brianscharp wrote:

The focus on "cases" is misleading for a number of reasons. The first problem is disparate levels of testing in different countries. Another problem is the definition of a "case". Does that mean reporting of symptoms or does it mean a positive test result? Another problem is the willingness of various regimes to report cases. It's easier for countries to fudge the numbers on "cases" than on actual deaths. Finally, we have very little data on how many people are infected with few or no symptoms. That might also depend on the perception of consequences for self reporting or getting tested without symptoms.

For all of those reasons, I think deaths per unit of population is the most reliable measure of severity in any country.

Join a National Hang Gliding Organization: US Hawks at ushawks.org

View my rating at: US Hang Gliding Rating System

Every human at every point in history has an opportunity to choose courage over cowardice. Look around and you will find that opportunity in your own time.

View my rating at: US Hang Gliding Rating System

Every human at every point in history has an opportunity to choose courage over cowardice. Look around and you will find that opportunity in your own time.

-

Bob Kuczewski - Contributor

- Posts: 8396

- Joined: Fri Aug 13, 2010 2:40 pm

- Location: San Diego, CA

Re: Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)

https://www.corriere.it/politica/20_mar ... resh_ce-cp

«The real death toll for Covid-19 is at least 4 times the official numbers»

Scroll to about 34:00.

Live: Gov. Cuomo Gives Update On Coronavirus Spread Across NY State | NBC News

«The real death toll for Covid-19 is at least 4 times the official numbers»

Nembro, one of the municipalities most affected by Covid-19, should have had - under normal conditions - about 35 deaths. 158 people were registered dead this year by the municipal offices. But the number of deaths officially attributed to Covid-19 is 31

di Claudio Cancelli Luca Foresti

«The real death toll for Covid-19 is at least 4 times the official numbers»shadow

In Nembro the almost deserted streets, the absent traffic, a strange silence is sometimes interrupted by the siren of an ambulance that carries with it the anxiety and worry that fill the hearts of all in these weeks. In Nembro every member of the community continuously receives news that he never wanted to hear, every day we lose people who were part of our lives and our community. Nembro, in the province of Bergamo, is the municipality most affected by Covid-19 in relation to the population. We do not know exactly how many people have been infected, but we know that the number of deaths officially attributed to Covid-19 is 31. We are two physicists: one who became an entrepreneur in the health sector, the other a mayor, in close contact with a very cohesive territory, where we know each other very well. We noticed that something in these official numbers did not come back right, and we decided - together - to check. We looked at the average of the deaths in the municipality of previous years, in the period January - March. Nembro should have had - under normal conditions - about 35 deaths. 158 people were registered dead this year by the municipal offices. That is 123 more than the average. Not 31 more, as it should have been according to the official numbers of the coronavirus epidemic.

The difference is enormous and cannot be a simple statistical deviation. Demographic statistics have their «constancies» and annual averages change only when completely «new» phenomena arrive. In this case, the number of abnormal deaths compared to the average that Nembro recorded in the period of time in consideration is equal to 4 times those officially attributed to Covid-19. If a comparison is made between the deaths that have occurred and the same period in previous years, the anomaly is even more evident: there is a peak of «other» deaths in correspondence with that of the official deaths from Covid-19.

In the hypothesis - not at all remote - that all citizens of Nembro have caught the virus (with many asymptomatic, therefore), 158 deaths would equate to a lethality rate of 1%. That is precisely the expected and measured lethality rate on the Diamond Princess cruise ship and - made proportionally by demographic structure - in South Korea. We have made exactly the same calculation for the municipalities of Cernusco sul Naviglio (Mi) and Pesaro using exactly the same methodology. In Cernusco the number of anomalous deaths is equal to 6.1 times those officially attributed to Covid-19, also in Pesaro 6.1 times. But even more staggering are the Bergamo figures, where the ratio reaches 10.4.

«The real death toll for Covid-19 is at least 4 times the official numbers»

It is extremely reasonable to think that these excess deaths are largely elderly or frail people who died at home or in residential facilities, without being hospitalized and without being swabbed to verify that they have actually become infected with Covid-19. Given the decline seen in the last few days after the peak, flock immunity has likely been attained in Nembro. To a certain degree, Nembro represents what would happen in Italy if everyone were infected by CoronaVirus, Covid-19: 600,000 people would die. The numbers of Nembro also suggest that we must take those official deaths and multiply them by at least 4 to have the real impact of Covid-19 in Italy, at this moment.

Our suggestion, therefore, is to take the data of the individual municipalities where there have been at least 10 official deaths due to Covid-19 and check if it corresponds to real deaths. Our fear is that not only the number of infected people have been largely underestimated due to the low number of swabs and tests carried out, and therefore the number of asymptomatics from the statistics have «disappeared», but that the case is also – through the data of the Municipalities - that of the dead. We are in the midst of an epoch-making event and to fight it we need credible data on the reality of the situation, disclosed transparently among all the experts and people who have to manage the crisis responsibly. Based on these data we can understand and decide what is right to do when it is required.

Scroll to about 34:00.

Live: Gov. Cuomo Gives Update On Coronavirus Spread Across NY State | NBC News

-

brianscharp - Contributor

- Posts: 304

- Joined: Tue Nov 11, 2014 12:49 pm

Re: Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)

https://www.statnews.com/2020/03/17/a-f ... able-data/

A fiasco in the making? As the coronavirus pandemic takes hold, we are making decisions without reliable data

By JOHN P.A. IOANNIDIS

MARCH 17, 2020

The current coronavirus disease, Covid-19, has been called a once-in-a-century pandemic. But it may also be a once-in-a-century evidence fiasco.

At a time when everyone needs better information, from disease modelers and governments to people quarantined or just social distancing, we lack reliable evidence on how many people have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 or who continue to become infected. Better information is needed to guide decisions and actions of monumental significance and to monitor their impact.

Draconian countermeasures have been adopted in many countries. If the pandemic dissipates — either on its own or because of these measures — short-term extreme social distancing and lockdowns may be bearable. How long, though, should measures like these be continued if the pandemic churns across the globe unabated? How can policymakers tell if they are doing more good than harm?

The data collected so far on how many people are infected and how the epidemic is evolving are utterly unreliable. Given the limited testing to date, some deaths and probably the vast majority of infections due to SARS-CoV-2 are being missed. We don’t know if we are failing to capture infections by a factor of three or 300. Three months after the outbreak emerged, most countries, including the U.S., lack the ability to test a large number of people and no countries have reliable data on the prevalence of the virus in a representative random sample of the general population.

This evidence fiasco creates tremendous uncertainty about the risk of dying from Covid-19. Reported case fatality rates, like the official 3.4% rate from the World Health Organization, cause horror — and are meaningless. Patients who have been tested for SARS-CoV-2 are disproportionately those with severe symptoms and bad outcomes. As most health systems have limited testing capacity, selection bias may even worsen in the near future.

The one situation where an entire, closed population was tested was the Diamond Princess cruise ship and its quarantine passengers. The case fatality rate there was 1.0%, but this was a largely elderly population, in which the death rate from Covid-19 is much higher.

Projecting the Diamond Princess mortality rate onto the age structure of the U.S. population, the death rate among people infected with Covid-19 would be 0.125%. But since this estimate is based on extremely thin data — there were just seven deaths among the 700 infected passengers and crew — the real death rate could stretch from five times lower (0.025%) to five times higher (0.625%). It is also possible that some of the passengers who were infected might die later, and that tourists may have different frequencies of chronic diseases — a risk factor for worse outcomes with SARS-CoV-2 infection — than the general population. Adding these extra sources of uncertainty, reasonable estimates for the case fatality ratio in the general U.S. population vary from 0.05% to 1%.

That huge range markedly affects how severe the pandemic is and what should be done. A population-wide case fatality rate of 0.05% is lower than seasonal influenza. If that is the true rate, locking down the world with potentially tremendous social and financial consequences may be totally irrational. It’s like an elephant being attacked by a house cat. Frustrated and trying to avoid the cat, the elephant accidentally jumps off a cliff and dies.

Could the Covid-19 case fatality rate be that low? No, some say, pointing to the high rate in elderly people. However, even some so-called mild or common-cold-type coronaviruses that have been known for decades can have case fatality rates as high as 8%when they infect elderly people in nursing homes. In fact, such “mild” coronaviruses infect tens of millions of people every year, and account for 3% to 11% of those hospitalized in the U.S. with lower respiratory infections each winter.

These “mild” coronaviruses may be implicated in several thousands of deaths every year worldwide, though the vast majority of them are not documented with precise testing. Instead, they are lost as noise among 60 million deaths from various causes every year.

Although successful surveillance systems have long existed for influenza, the disease is confirmed by a laboratory in a tiny minority of cases. In the U.S., for example, so far this season1,073,976 specimens have been tested and 222,552 (20.7%) have tested positive for influenza. In the same period, the estimated number of influenza-like illnesses is between 36,000,000 and 51,000,000, with an estimated 22,000 to 55,000 flu deaths.

Note the uncertainty about influenza-like illness deaths: a 2.5-fold range, corresponding to tens of thousands of deaths. Every year, some of these deaths are due to influenza and some to other viruses, like common-cold coronaviruses.

In an autopsy series that tested for respiratory viruses in specimens from 57 elderly persons who died during the 2016 to 2017 influenza season, influenza viruses were detected in 18% of the specimens, while any kind of respiratory virus was found in 47%. In some people who die from viral respiratory pathogens, more than one virus is found upon autopsy and bacteria are often superimposed. A positive test for coronavirus does not mean necessarily that this virus is always primarily responsible for a patient’s demise.

If we assume that case fatality rate among individuals infected by SARS-CoV-2 is 0.3% in the general population — a mid-range guess from my Diamond Princess analysis — and that 1% of the U.S. population gets infected (about 3.3 million people), this would translate to about 10,000 deaths. This sounds like a huge number, but it is buried within the noise of the estimate of deaths from “influenza-like illness.” If we had not known about a new virus out there, and had not checked individuals with PCR tests, the number of total deaths due to “influenza-like illness” would not seem unusual this year. At most, we might have casually noted that flu this season seems to be a bit worse than average. The media coverage would have been less than for an NBA game between the two most indifferent teams.

Some worry that the 68 deaths from Covid-19 in the U.S. as of March 16 will increase exponentially to 680, 6,800, 68,000, 680,000 … along with similar catastrophic patterns around the globe. Is that a realistic scenario, or bad science fiction? How can we tell at what point such a curve might stop?

The most valuable piece of information for answering those questions would be to know the current prevalence of the infection in a random sample of a population and to repeat this exercise at regular time intervals to estimate the incidence of new infections. Sadly, that’s information we don’t have.

In the absence of data, prepare-for-the-worst reasoning leads to extreme measures of social distancing and lockdowns. Unfortunately, we do not know if these measures work. School closures, for example, may reduce transmission rates. But they may also backfire if children socialize anyhow, if school closure leads children to spend more time with susceptible elderly family members, if children at home disrupt their parents ability to work, and more. School closures may also diminish the chances of developing herd immunity in an age group that is spared serious disease.

This has been the perspective behind the different stance of the United Kingdom keeping schools open, at least until as I write this. In the absence of data on the real course of the epidemic, we don’t know whether this perspective was brilliant or catastrophic.

Flattening the curve to avoid overwhelming the health system is conceptually sound — in theory. A visual that has become viral in media and social media shows how flattening the curve reduces the volume of the epidemic that is above the threshold of what the health system can handle at any moment.

Yet if the health system does become overwhelmed, the majority of the extra deaths may not be due to coronavirus but to other common diseases and conditions such as heart attacks, strokes, trauma, bleeding, and the like that are not adequately treated. If the level of the epidemic does overwhelm the health system and extreme measures have only modest effectiveness, then flattening the curve may make things worse: Instead of being overwhelmed during a short, acute phase, the health system will remain overwhelmed for a more protracted period. That’s another reason we need data about the exact level of the epidemic activity.

One of the bottom lines is that we don’t know how long social distancing measures and lockdowns can be maintained without major consequences to the economy, society, and mental health. Unpredictable evolutions may ensue, including financial crisis, unrest, civil strife, war, and a meltdown of the social fabric. At a minimum, we need unbiased prevalence and incidence data for the evolving infectious load to guide decision-making.

In the most pessimistic scenario, which I do not espouse, if the new coronavirus infects 60% of the global population and 1% of the infected people die, that will translate into more than 40 million deaths globally, matching the 1918 influenza pandemic.

The vast majority of this hecatomb would be people with limited life expectancies. That’s in contrast to 1918, when many young people died.

One can only hope that, much like in 1918, life will continue. Conversely, with lockdowns of months, if not years, life largely stops, short-term and long-term consequences are entirely unknown, and billions, not just millions, of lives may be eventually at stake.

If we decide to jump off the cliff, we need some data to inform us about the rationale of such an action and the chances of landing somewhere safe.

John P.A. Ioannidis is professor of medicine and professor of epidemiology and population health, as well as professor by courtesy of biomedical data science at Stanford University School of Medicine, professor by courtesy of statistics at Stanford University School of Humanities and Sciences, and co-director of the Meta-Research Innovation Center at Stanford (METRICS) at Stanford University.

Join a National Hang Gliding Organization: US Hawks at ushawks.org

View my rating at: US Hang Gliding Rating System

Every human at every point in history has an opportunity to choose courage over cowardice. Look around and you will find that opportunity in your own time.

View my rating at: US Hang Gliding Rating System

Every human at every point in history has an opportunity to choose courage over cowardice. Look around and you will find that opportunity in your own time.

-

Bob Kuczewski - Contributor

- Posts: 8396

- Joined: Fri Aug 13, 2010 2:40 pm

- Location: San Diego, CA

Return to Free Speech Zone / Off-Mission Discussions

Who is online

Users browsing this forum: No registered users and 4 guests